“The best thing to sell cars is a stopwatch saying that you’re faster than the other guy.”

– Giampaolo Dallara

Dallara is a force in modern motorsport but typically prefers to let its customers bask in the limelight. The company’s work is seen by millions and relied upon by the hundreds of drivers who put their safety in the hands of Dallara engineers. Dallara designs have won the Daytona 24 and 24 Hours of LeMans. A Dallara first won the Indy 500 in 1998 and has been IndyCar’s exclusive manufacturer since 2012. Dallara open-wheel cars have dominated Formula Three championships around the world for decades.

Recently, Speed Journal Principal Jeff Francis journeyed to Dallara’s headquarters near Parma, Italy. This is the second of a three-part series, exploring the Dallara Academy that explains the science behind race car design and engineering. In the first part, The Speed Journal goes back in time for a look at Dallara’s founding and history. The third part samples the Dallara Stradale, the company’s road-going race car.

The Dallara Academy

In 2018, Dallara opened its Academy – a facility designed to welcome guests, encourage education, and share the Dallara story. Mr. Dallara wanted an “academy” – not a museum. He wanted a place where people can learn. Dallara staff contributed ideas. Mr. Dallara spearheaded a design committee that included professors and teachers.

While the Academy has a remarkable display area for cars, interactive learning displays give guests a chance for hands on learning. Dallara is deeply invested in growing the next generation of engineers, designers, and technicians. Showing young people differences in material choice and aerodynamic shapes helps them to understand trade-offs of weight and strength. Simulations help them to experience braking effort and see how downforce and drag play a part in race car setups.

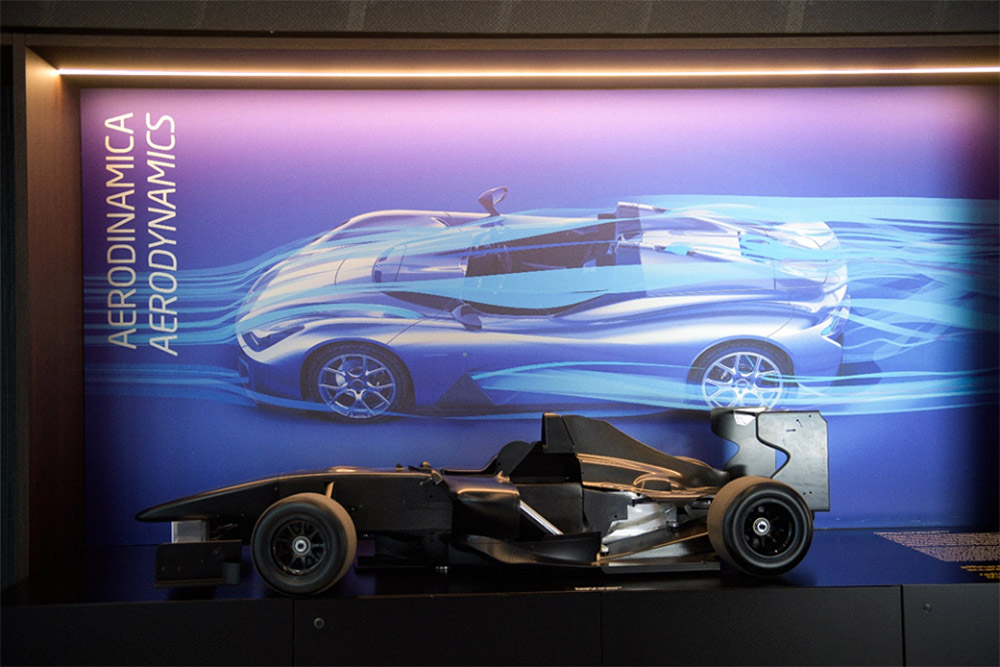

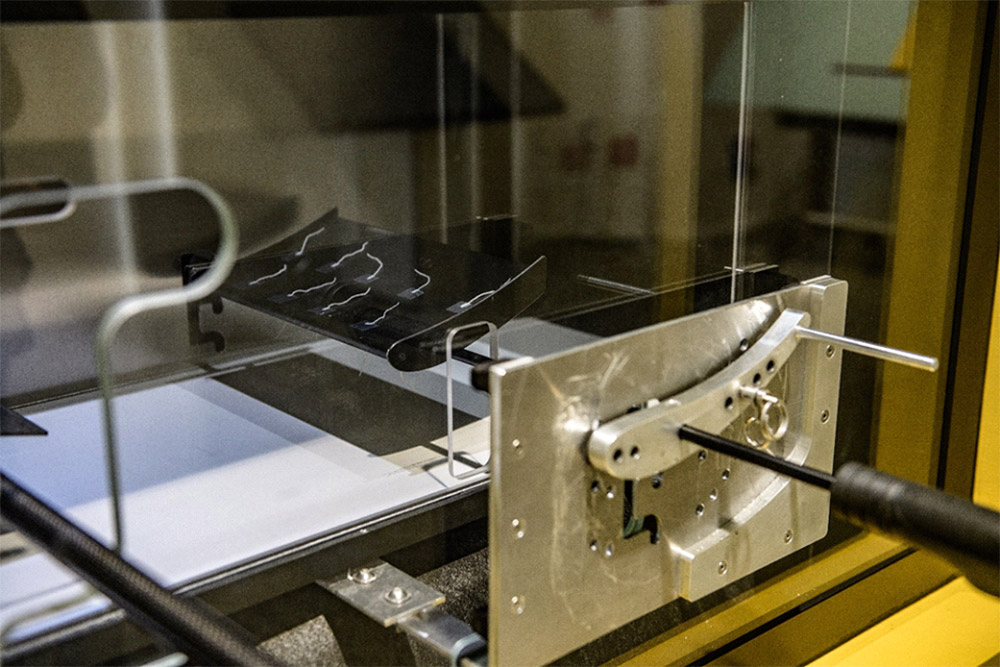

The Academy features composite materials, aerodynamics, vehicle dynamics. Interactive experiments explain how physics are related to racing cars behavior and race car design.

The layout is similar to what a science center or museum for kids might feature, but everything is focused on car design and racing. The first area focuses on materials by allowing a guest to handle four different materials: steel, aluminum, carbon fiber, and carbon fiber with aluminum honeycomb. The guest applies force to see how they deform.

The Academy shows how different materials serve different needs and explains how Dallara works to determine what combination of materials works best for the need. Carbon fiber is strong and light, but expensive and complicated and difficult to make in high volumes. For a Formula One car, speed and safety and weight is more important than cost, but some race series attempt to keep budgets more manageable for customers so there are trade-offs involved. Dallara’s composite services are 70% labor and 30% materials, showing the amount of brainpower and labor involved in finding the optimal design and making parts.

Another demonstration compares two similar race cars with nose cones made of different materials (metal and rubber). The nose cone drops against a fixed surface and embedded sensors measure the force from each. The data shows energy absorption and Dallara explains how it manages materials to collapse in certain ways and dissipate impact energy away from the driver.

An aerodynamics station helps illustrate drag and downforce. Vents create airflow and guests experiment with different winglet shapes. Once they understand downforce and drag, they adjust race cars configurations to see the implications of different setups at widely varying tracks of Monte Carlo, Monza, and Barcelona. When Dallara has student groups, kids are divided and compete with each other for fastest lap times based on their set-ups.

Students even sit in a mock cockpit and feel the heavy steering and braking effort required during a race. The modules are calibrated with actual Dallara data. The idea is to give a glimpse into the world of race car design and an appreciation of the engineering variables and resulting impacts for the driver.

The Academy also includes Mr. Dallara’s first drafting table to show how cars were designed with pens and without computers. Dallara wants guests to understand how things were made in the past and appreciate the core principles of design.

Dallara is a part of a consortium that provides more formal education programs, working with local universities to mix academic experts and Dallara staff. Classroom space, eight courses and a university degree program make the Academy a true institution of learning. The efforts are partially a project of passion, but also an investment in future employees for employers broadly throughout the Motor Valley.

The Academy also gives Dallara a place to welcome customers and enthusiasts. Previously, its customer base was only manufacturers and racing teams. As Dallara has moved into making road cars under its own name, having a place for potential customers to visit and learn more about the Dallara story is key to continuing the company’s growth.

A Gallery of Dallara Projects

The gallery of Dallara work is testament to the breadth and depth of the company’s touch. On The Speed Journal’s visit, an IMSA Wayne Taylor Racing DPI that won the 24 Hours of Daytona in 2019 sat across the room from a HAAS Racing Formula One car and a Formula E car. A Lamborghini Miura and Fiat Bertone X1/9 race car sat near a 2002 Oreca LeMans racer and a pair of Lancia competition cars.

The collection includes the first car to ever carry a Dallara badge. Designed in 1972, the SP1000 is low, light, streamlined and covered with a single piece of fiberglass bodywork. Its small 4-cylinder engine makes 120 horsepower and the car weighs 480kg (1058 pounds) –small numbers good for 240 kph (149mph) in a straight line at Monza. The rules required that cars had at least 2 seats, so Mr. Dallara designed with three seats to put driver in the middle and optimize weight distribution. The car was very fast and naturally, regulations changed after the season to close the loophole.

Two examples of open-wheel F3 race cars compared aluminum and carbon fiber chassis. A red and white #6 with an aluminum chassis won the Italian championship in 1980. Nearby, the #7 1985 Dallara F385 was the first carbon fiber chassis Formula Three car made. The visual difference is striking – the aluminum chassis is more angular while the carbon fiber chassis has more curves and more sophisticated shape.

Dallara is rightfully proud of its safety record. Hundreds of drivers implicitly trust Dallara when climbing aboard a car of Dallara design. When it goes wrong, the results can be spectacular. 17-year old Sophia Floersch had a massive F3 crash at Macau GP in 2018. She went off at high speed – estimated at 276kph (171 mph) – into catch fencing. She damaged her spine but survived. Dallara uses her reconstructed car to explain how safety measures are incorporated into car design. It is a real life illustration of academic lessons demonstrated in the Academy. From the hospital, Sophia said “Thank you Dallara for making such a safe car because you saved my life.” She later visited Dallara to thank Mr. Dallara and the company and her racing career continues.

The KTM crossbow is an example of collaboration with original equipment manufacturers. KTM historically made motorcycles but wanted to design and produce their first car, so KTM and Dallara worked together to make the four wheeled motorbike to kick off the X-Bow. Almost everything was made out of carbon fiber for the one hundred unit special edition. KTM thanked Dallara by giving them car number one hundred.

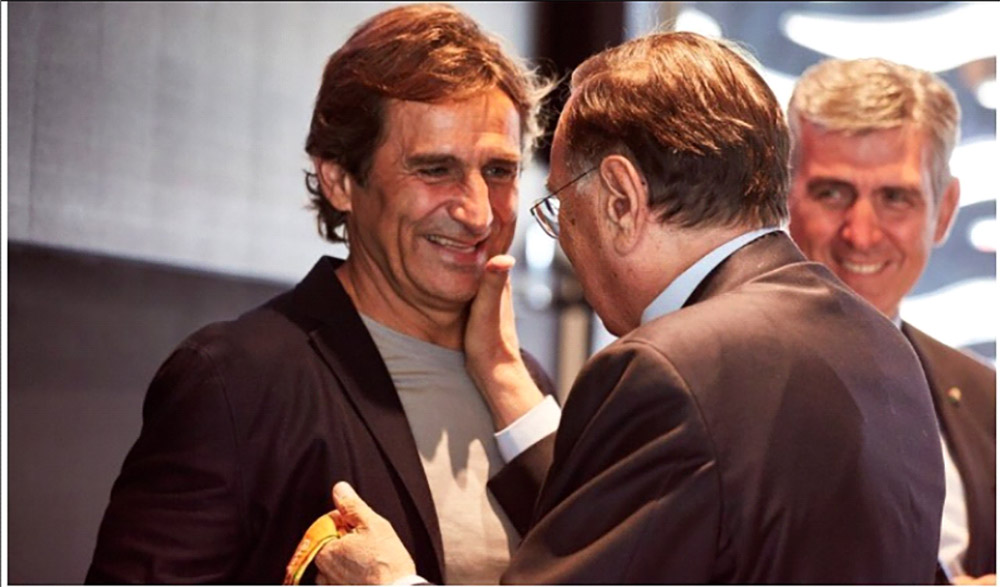

The only three-wheeler in the display is a carbon fiber competition wheel chair designed with open-wheel racing legend Alex Zanardi. Zanardi lost his legs in a terrible 2001 Indycar accident but continued racing in paralympic events. Dallara made a bicycle for Zanardi and he took it to victory in the 2012 London Paralympics. Zanardi even went into the wind tunnel to help find the best shape. At the Academy’s grand opening, Zanardi thanked Dallara by giving Mr. Dallara his gold medal from 2016 Rio de Janeiro. Together, Dallara and Zanardi developed a bicycle called the Z bike for other Paralympians.

After touring Dallara and spending time at the Dallara Academy and with Dallara staff, the racing passion is palpable. Staff frequently reference Mr. Dallara and his leadership which sets the tone for the entire company. The beneficiaries are racing teams and drivers, manufacturers and customers and students who find their own passion and a professional path in the Motor Valley. Next time you watch a race or slide behind the wheel of a race car or drive a high performance road car, remember that you might be connecting with Dallara racing DNA that comes from Mr. Dallara and the Dallara team in Parma.

The Speed Journal would like to thank Dallara and the Dallara team for their time and hospitality.