Visiting the Porsche museum in Stuttgart, Germany is really more like visiting a friend with a huge car collection spanning seven decades who has the means and skills to maintain it, drive the cars constantly, loan them out to friends, and actually have more cars than space to store them.

As Jeff Francis arrived during his European tour for The Speed Journal, he was greeted by a pair of Porsche 918 road cars parked in front of the Porsche dealership in the heart of Zuffenhausen. That’s a good start to any visit.

Zuffenhausen is the district in the broader city of Stuttgart that serves as Porsche’s worldwide headquarters. The main traffic circle in Zuffenhausen is known as the Porscheplatz and it is surrounded by Porsche’s main production factory and the Porsche Museum.

The Porsche museum itself is an architectural wonder of metal and glass. Construction began in October 2005 and the museum was completed and open to the public in January 2009. Three main columns support the main space which floats above the ground. A reflective surface beneath the floating rectangle highlights anything parked beneath.

The traffic circle in front of the museum features a sculpture installed in the fall of 2015. Three different generations of white Porsche 911 models are mounted on 82-foot tall white metal spikes in the traffic circle. It creates a striking anchor for the center of the Porsche universe, surrounded by the Porsche museum, the Zuffenhausen factory and the Porsche dealership for Stuttgart.

The three spikes themselves represent three different places of significance for Porsche. One points to Gmünd in Austria where Ferry Porsche made the first cars under the Porsche name. Another is a nod to Porsche’s second plant in Leipzig, Germany. The other recognizes Weissach, the center of Porsche engineering and motorsports.

While the museum collection has 600 total cars, the museum itself can only accommodate 60 or so cars at any given time. Displays change regularly as cars are being maintained, restored, rotated through storage, exhibited at vintage events, or on loan for display elsewhere. Porsche even calls this active exercise of its corporate history a “rolling museum.”

Porsche recognizes the marketing value of taking its jewels to events around the world. Historic race cars in particular are featured at events in Porsche’s major markets, including events in the United States such as the Rennsport Reunions held every few years. Fans gets to see the cars but more importantly, they get to see and hear the cars in motion.

The museum staff place a priority on keeping them in running order. Some are in various states of restoration or repair, but the vast majority are runners. The workshop at the Museum is visible through a large glass wall for visitors when picking up entry tickets. The initial impression of a working garage sets the tone for the rest of the tour.

So, what caught the eye of The Speed Journal during the visit?

Before there was a “Porsche” company that made and sold cars to customers, Professor Ferdinand Porsche designed and engineered automobiles. In 1938, he was involved in a project to build a racecar for a planned Berlin to Rome race. Known as the Type 64, three cars were built before World War II intervened and the race never happened. One car was scrapped early after a traffic accident and another was scrapped after American troops apparently found it in Austria, chopped off the top, and drove it until the engine seized. The remaining car was kept by Porsche who tweaked it a bit after the war. Among other things, he added his name to the nose which made it the first car to bear his name. In 1949, as the new Porsche company was getting started, it was sold to a private amateur racer.

Stepping off the escalator into the display area, one the first things that catches the eye is a shiny, bare aluminum sculpture. It is a replica of the Type 64, made in connection with the opening of this new museum facility in 2009. It was constructed without benefit of original blue prints or reference to the original car, and it has never been a rolling, functioning car.

Porsche commissioned the sculpture because it was the first car to bear the Porsche name and its design language is instantly recognizable as a Porsche.

Nearby sat Porsche 356 number one. The one and only 356 prototype was built in 1948 in Gmünd, Austria. The silver 2 door open roadster with a modest flat four-cylinder engine making only 35 horsepower. The prototype clearly established the distinctive Porsche styling cues that tie subsequent decades of Porsches together. This is where it all started for Porsche as a marque.

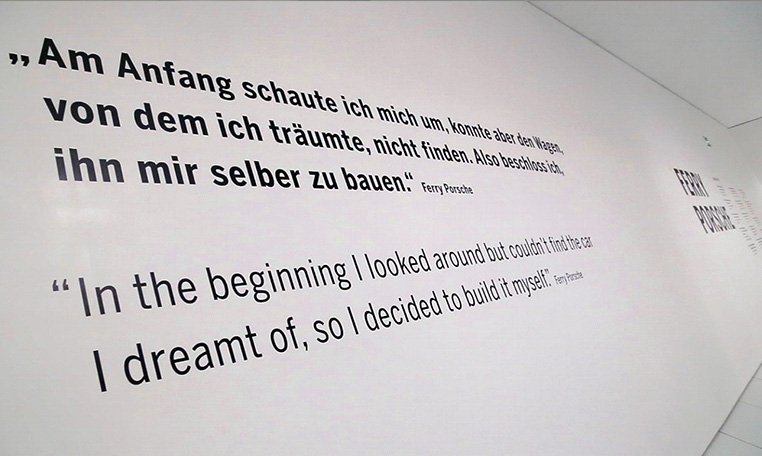

Ferdinand Porsche had the vision and the engineering knowledge to make things happen. His famous quote is inscribed on a nearby wall – “In the beginning I looked around but couldn’t find the car I dreamt of, so I built it myself.”

Further along were examples of Porsche cars from the 1950s and 1960s. Road cars, race cars and even a Porsche powered tractor gave testament to the rapid growth of the marque. The early cars clearly bear Ferdinand Porsche’s fingerprints.

Among this batch sits an open wheeled Porsche 804. The 1962 French Grand Prix was Porsche’s only Formula One victory and it came courtesy of Dan Gurney and the Porsche 804. The circuit near Rouen was bumpy and difficult and Gurney was feeling ill. Others faltered, but Porsche had reliability and Gurney’s skill and wits. Formula One was already escalating in expense, so Porsche pulled the plug on its open wheel effort after 1962. The museum chassis is the last of four built, but it never raced in competition.

After withdrawing from Formula One, Porsche refocused its efforts on sportscars. One result on exhibit was the 1964 Porsche 904 Carrera GTS Coupe. Not only is it incredibly beautiful and the body lines timeless, it gives a hint of the purpose-built race cars to come. Only 106 examples were made, however, and as they are quite desirable, most are too valuable to see a race circuit in anger anymore.

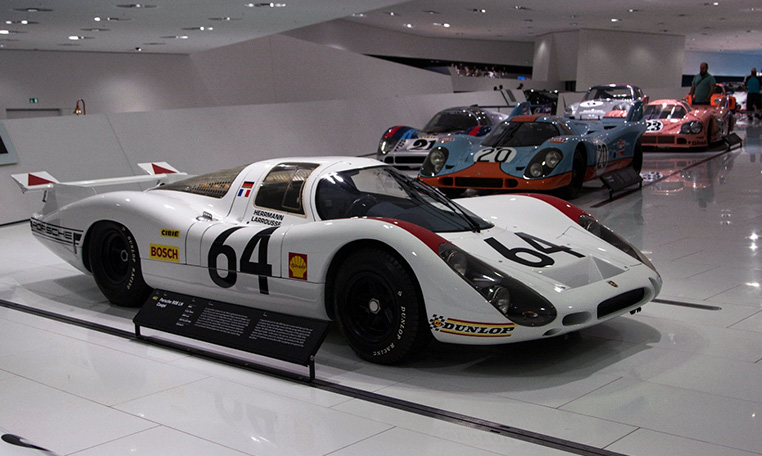

Within sight of the early cars, the mighty prototypes of the late 1960s and 1970s keep vigil. It is difficult to imagine that Porsche went from a 356 race car that won its class in 1951 (the first Le Mans win for Porsche) to long-tail, 12 cylinder 917 prototypes that set high speed records only a few years later. The 917 family arguably put Porsche on the racing map as it allowed Porsche to complete for overall wins at the biggest races in the world. Success on the track, exotic shapes, and interesting variants that ruled race tracks across the world – no wonder the Porsche 917 still commands attention at the race track as well as the auction block.

Not one, not two, but three 917 models were on display for Speed Journal inspection. A short tail 917 bore iconic blue and orange Gulf colors which is probably the most well-known model. However, a longtail 917 specifically designed for high speed that ran at Le Mans in 1970 and 1971 was on display as well. It was fast, but fragile and failed to finish either time. The legacy, however, is more about the stunningly beautiful shape than specific race results. Out of six originally built, only three still exist.

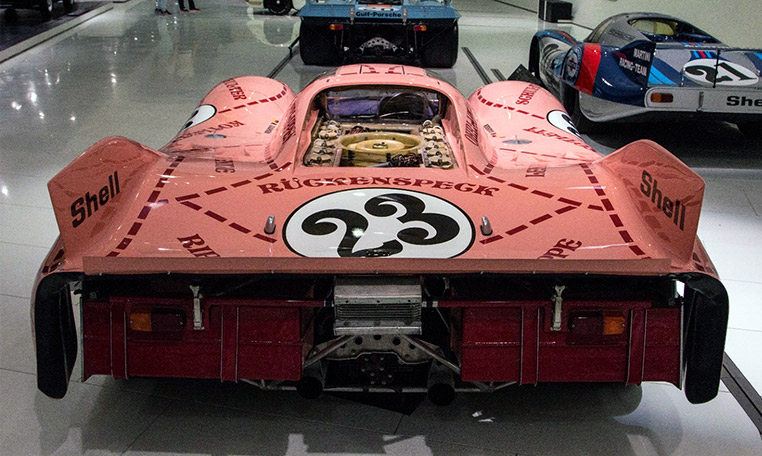

Even more rare is the 917/20 known more famously as the “Pink Pig.” A one-off aerodynamic exercise that sought to combine the best of the short and long tail configurations, the Pink Pig takes its name from the livery that features cuts of meat. It ran in only the 1971 Le Mans and failed to finish due to an accident. The distinctive livery and its wide, flat, rounded shape have made it a Porsche racing milestone and a fan favorite despite the lack of a successful race result record.

Race cars from all decades adorn different corners of the museum. The muscular 911 RSR from the late 1970s, different versions of the 944 and the prototype 956 in the 1980s, the Le Mans winning 911GT1-98 from the 1990s, and the RS Spyder from the 2000s all give testament to the breadth and depth of Porsche racing. Some successes were claimed by full factory run teams and others were claimed by private customers.

A Porsche hallmark is the close link between success on the race track and road car development. Engineering expertise builds knowledge and technological developments. One clear example was the display featuring four generations of 911 Turbo road cars, turning in synch on rotating platforms. Turbo technology has powered many Porsches over the years and 911 Turbo has made its own mark on Porsche’s timeline.

As well-known as the Porsche 911 Turbo might be, there is another example of engineering knowledge transfer that might not be as well known. Starting in 1997, Harley-Davidson and Porsche embarked on a joint venture to make motorcycle powertrain components. In 2002, Porsche assisted with development of the V-2 “Revolution” Engine that went into the V-Rod model and produced 120 horsepower. A complete motorcycle is on display in the museum to pay homage to the effort.

The Porsche museum is short on memorabilia, artifacts and even multimedia gizmos. There is little in the way of story boards or photos on the walls. It a distinctly minimalist approach that focuses all the attention on the cars and displays. The exhibits speak for themselves.

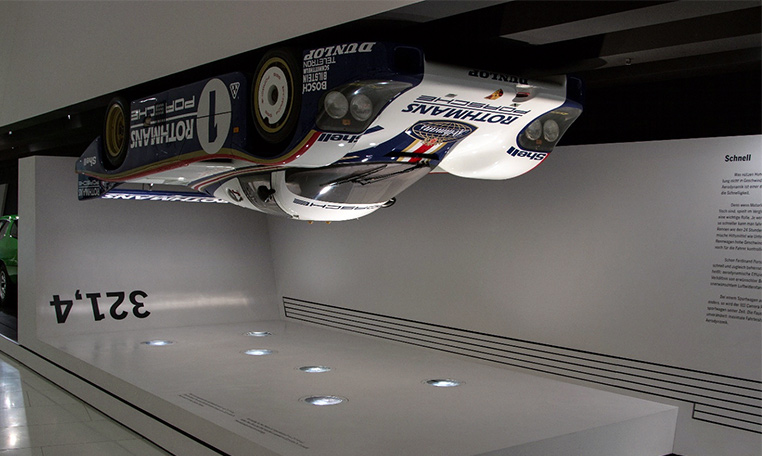

How does Porsche make a point about the power of aerodynamics? It mounts a 956 prototype upside down on the ceiling to make the point that the car produces downforce to stick the car to the racing surface. In theory, the car produces sufficient downforce to glue the car to the ceiling if it were able to run upside down. The visual makes a more powerful statement than a technical discussion of the physics.

Likewise, Porsche shows the scale of success on the race track by suspending hundreds of trophies to float in the air at different heights and depths – so many different types of trophies from different races through different decades. The visual arrangement makes a more powerful statement than a listing of victories on the wall.

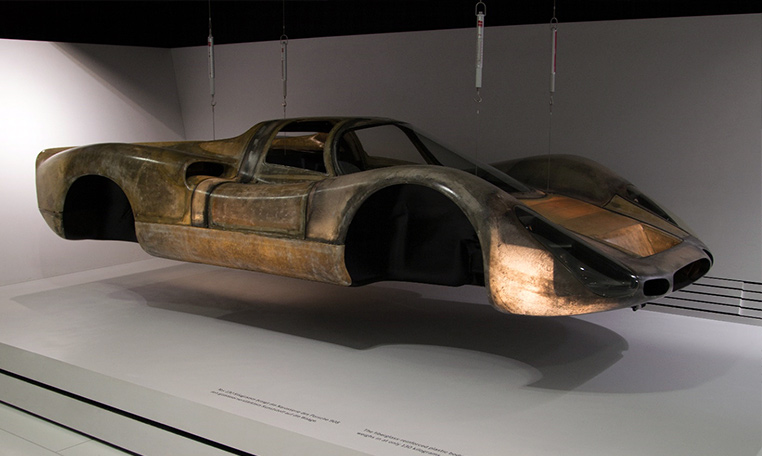

Similarly, Porsche demonstrates the value of lightness by suspending the fiberglass body of a Porsche 908 race car from the ceiling by four wires with only the modest note that the body weighs 130 kilograms (286 pounds). The negative space around the suspended body makes it appear to float.

A black Porsche 918 prototype that set a track record on the Nürburgring sat alone in the middle of a highly reflective floor. The modesty of display forces the visitor to focus on the car alone.

Just around the corner from the 918 is the race car cousin, the 919. In 2014, Porsche returned to top-tier prototype sportscar racing with the hybrid. The 919 Hybrid on display is the race winner from the 6 Hours of Sao Paulo, the first win for the 919. It is preserved just as it finished the race, complete with scratches, dents, and rub marks.

The museum 919 was appropriately parked to anchor a line of other significant race cars, including the 911 hybrid that ran in 2010 and 2011 as a test bed for hybrid technology. A green and yellow 911 that found success at the Nürburgring 24 came next followed by the yellow and red Penske RS Spyder. Each is a significant story on its own, but together they represent an incredible decade of accomplishment.

A bit further along was the Francis favorite – the single roadgoing version of the 1998 Porsche GT1-98. It was the only one made and the only one in existence. The pure white car even carries its registration numbers on its nose and rear license plate. Prior GT1 race cars had sought to stay somewhat faithful to the 911 road car platform, but competition on race tracks required a move to a bespoke race car. The GT1-98 was made out of carbon fiber, weighed less and used a twin-turbo flat six-cylinder engine to make it go. While the single road car was necessary to comply with regulatory requirements, none were made for sale so the car often considered the pinnacle of 911 evolution remained elusively out of reach for customers.

As a sign of how fluid the museum’s displays are, Francis did a walkthrough and found the GT1-98 road car across from a green 911GT1-98 race car originally run by the Zakspeed team. When he returned later to record a video piece, the Zakspeed car was gone.

After a few hours wandering the museum, a short escalator ride back to the main street level leads to the Boxtenstopp café to refuel with lunch. At the base of the escalator, the workshop that services the museum cars is clearly visible through a wall of windows. Dozens of cars are housed in the workshop in various states of service, storage or awaiting attention. After an enjoyable lunch, The Speed Journal spoke with Benjamin Marjanac at Porsche who provided an overview on the museum’s operations and priorities. Fittingly, the interview took place next to the Porsche 911GT1-98 that won the 1998 24 Hours of Le Mans.

Any automotive enthusiast visiting Germany will find themselves drawn to Stuttgart given the strong Porsche and Mercedes presence. Those that visit the Porsche museum will find a compelling selection of Porsche history that may look very different than the next time they visit.

For those that are unable to visit Stuttgart, keep an eye out for the Porsche rolling museum as they bring the cars to you.

The Speed Journal wishes to thank Porsche and the museum staff for kindly hosting our visit. We look forward to a return visit at some point.